As artists, we strive to find a deeper understanding of art through the experience of making. And as artists we continually search for how we can fit into the conversation of art that has continued for thousands of years. To better understand how we work, and how we can get closer to where we need to be can be a lifelong journey. A journey that has taken artist Jimi Gleason from Orange County to San Francisco, to New York, and back again. He certainly hasn't been afraid to take it.

I've known Jimi Gleason for about 15 years. As an artist, he's someone I've looked up to for a long time. To me, he's someone who has "made it". One of the most friendly and generous people I know, it's easy to like Jimi. Through the course of our visit, I discovered that he and I share many ideas and beliefs about art. Beliefs that he and I see as truths. Also, it's only been in recent years that I discovered that Jimi was a studio assistant to another art hero of mine, Ed Moses. It's no wonder he and I share some of the same beliefs.

Over the years we've talked about doing a studio visit, and even though numerous articles have been written about Jimi's work, I still wanted to document and share my experience of visiting his house and studio in Costa Mesa.

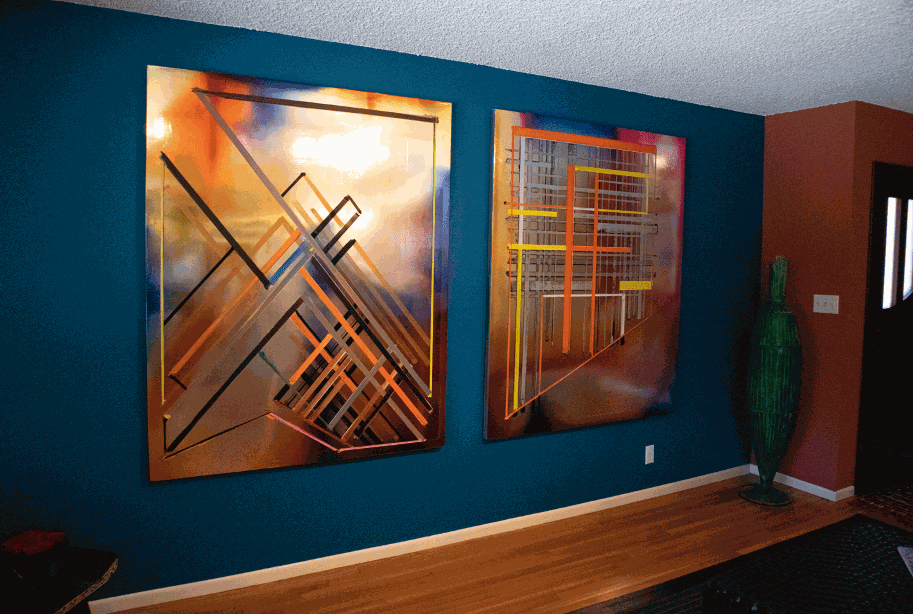

As I pulled up, I was greeted by Jimi and his dogs Porsche and Blue. After I passed the dogs' "security" check I was welcomed into the house. Jimi's impeccably arranged and beautiful house is lined with his paintings on just about every wall, where they fit perfectly. Two large paintings that I was particularly drawn to is where we started our conversation.

Jimi Gleason: "These paintings were from last spring into summer. I took the time last year to open everything up and just experiment with whatever I had at my hands." The COVID lockdowns gave Jimi time to do that. To, "get out some brushes and draw into it" as he puts it. Jimi went on to talk about the grid-work of these paintings.

JG: "You know, the grid has been around forever, but these in particular were pretty much how Ed Moses made his track paintings. So, they totally are derivative from Ed. And Manhattan is a grid, so that's just really stuck in my head too."

Ed Moses and New York came up numerous times throughout our conversation. Jimi went into describing his process for making his paintings, which is very, very involved. Numerous layers of enamel paint, silver nitrate, matte paint, automotive paint, and interference paint all go into making Jimi's work.

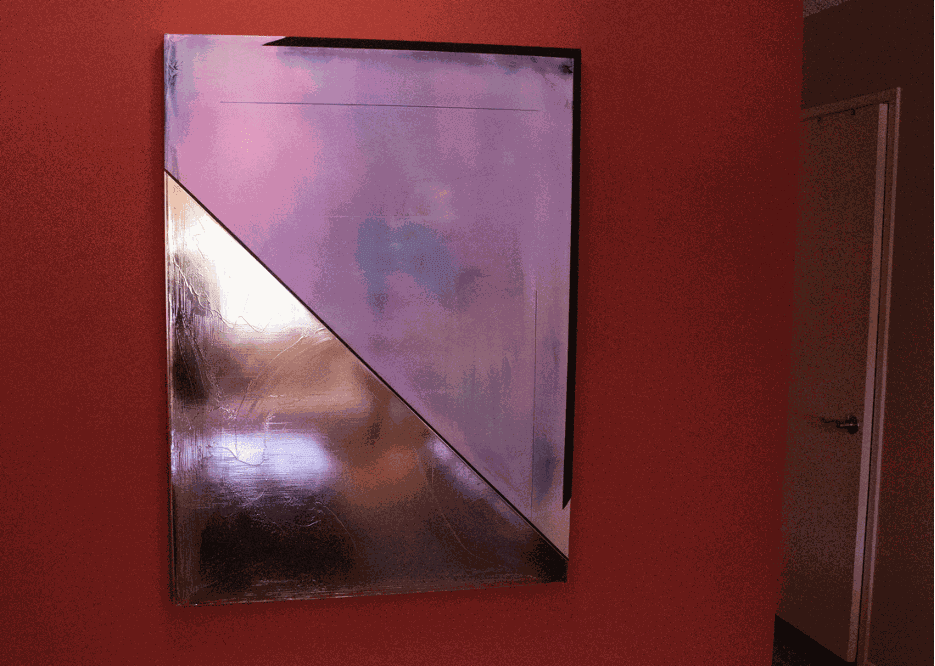

In most of Jimi's current painting's there is a strong diagonal running through the composition, and I was surprised to learn that the origins of it come from Jimi's love of aviation. A few of his friends who are pilots have taken him up a few times.

JG: "That diagonal to me is landscape-like if you're in an airplane and making a hard bank. I'm not a pilot but I Iike aviation a lot. Back in 1978, I lived off Jeffrey Rd. back in North Irvine, right next to the Marine Corps air base. Back then you could pull off the side of the road which was not too far from one of their runways. I used to love to sit there in my car and watch them touch and go off the runway."

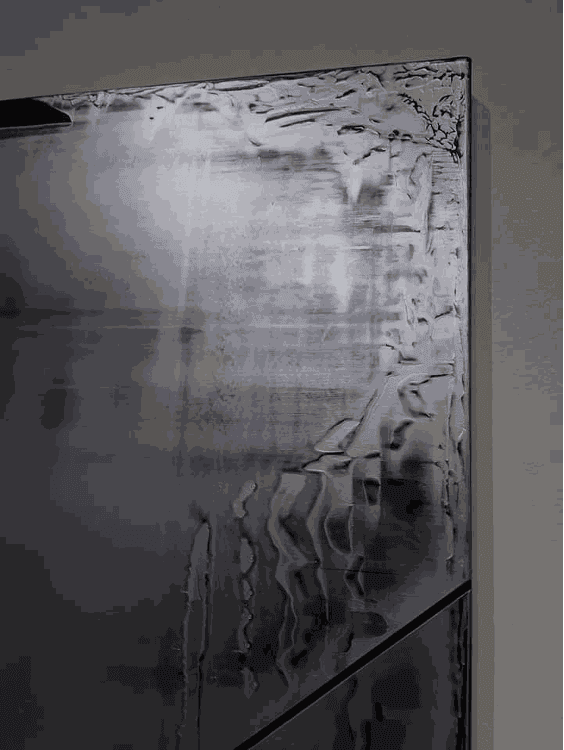

We went on to talk about Jimi's use of interference paint. In the painting above, there is the stark contrast between materials bordered along that sharp diagonal line. Yet, there is the underlying texture that's continuous throughout the whole piece that acts as a unifier. The interference colors offer Jimi an easier path towards multiple value shifts and a wider range of texture that differs from the silver nitrate. The soft gossamer effect of that paint and all the properties it reveals to Jimi, to the hard, opaque, and high reflectivity of the silver nitrate. Those two contrasts represent another influence of Jimi's; his love of the ocean.

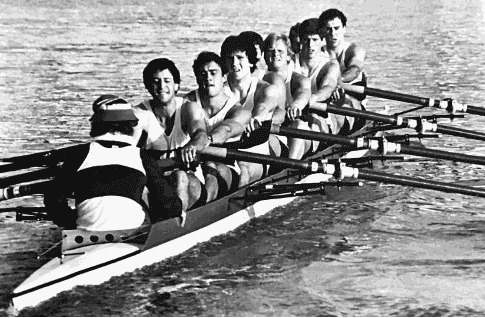

Since he first started surfing in 3rd grade and on through rowing crew at Orange Coast College and at UC Berkeley, Jimi's fascination with water comes through in these subtle moments found in his paintings.

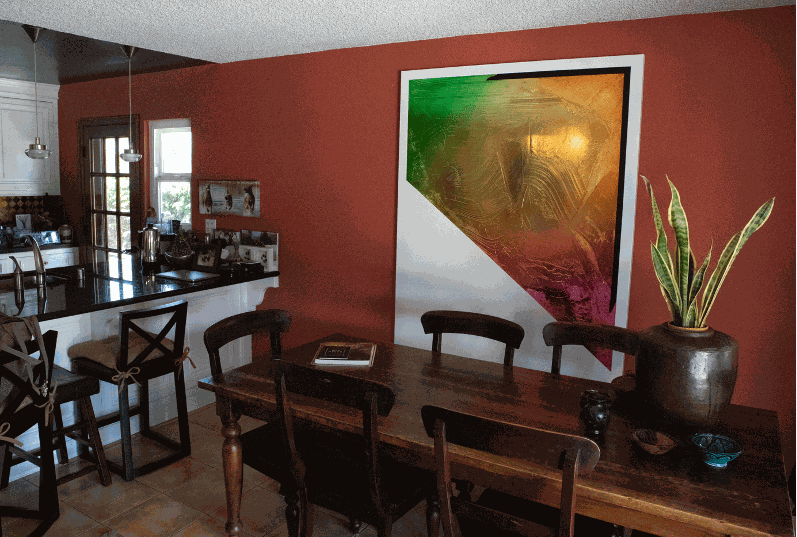

Jimi then has the ability to flip the script with his latest paintings that I described as his White Void paintings. The texture and shine of the color over the silver nitrate is isolated to a shape that has emerged from the aviation diagonal and is encased by a smooth white.

Influences like water and flying seep out unconsciously in Jimi's work, and I suspect most artists will tell you, that's what we're aiming for. When talking of influence Jimi says, "It's hard not to get out of your brain what I've seen for the last 40 years. Ellsworth Kelly, Larry Bell, Ed Moses, Joan Mithcell, Gerhard Richter." And as we moved slightly into the subject of art history, we agree that the baggage of art history that artists have the burden of carrying with them when making their work is ok. And if the influences of our mentors are clearly visible in our work, that's ok too.

Influence can also come in the form of outside processes. After a few years of printmaking at the Art Institute of San Francisco, Jimi moved to New York in 1987. He was invited by his high school friend Matt Sees, who was an accomplished photographer with a studio, and remains a successful photographer in Manhattan to this day. Jimi lived in Matt's photo studio from 1987 until 1991. He worked as a photo assistant for Matt where Jimi learned all the ins and outs of the photo developing process.

JG: "Pulling polaroids, and that squishy, emulsive edge; that became a foundation for me to have this band around my paintings, and sort of help me get my style. So, the edge has always been a really important part of my paintings because it all derives from photography. I think without being a photo assistant I would have never gotten that. Who knows what I'd be doing now!" Jimi had to get away from photography to realize that there are things about it that he needed to recapture and insert back into his paintings. The influence of that juicy emulsion of the photo process and working with silver gelatin prints is clear.

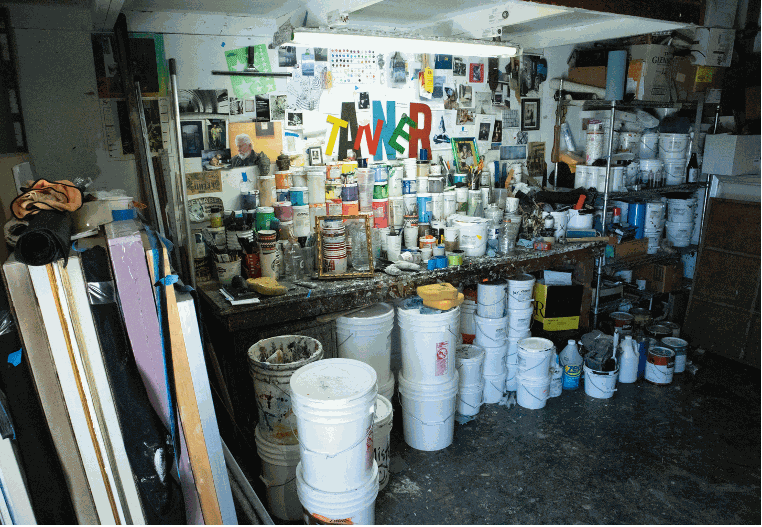

We then moved out into Jimi's backyard. He has an area set aside for himself outside where all his paintings see their start. Seeing that idea first from Ed Moses, he can do all the splashy, dirty work outside in clement weather. Jimi and I both agree that clement weather is in abundance in Southern California!

He then continues the work in his garage studio. A studio that's clearly been used, and rich in evidence that it has been for decades. He showed me various tools and materials that go into making his work, including dog screen that he uses as a texturizing tool, trowels with nubs at the end to create texture, and a hollow-core bedroom closet door that has acted as a table since 1998.

After the tour of his garage and showing me various paintings he has stored there, our conversation came around to the subject of meaning in Jimi's work and painting in general. It can be argued that contemporary painters are working with the same ideas that have been floating around for the last 100 years or more. As Jimi puts it, "People have said it all before, and we're really just rehashing." He and I have both had moments where we've read things past artists have said with the striking realization, they feel the same about making art as we do. And for both of us, that kinship is very comforting. To know that Jasper Johns, or Phillip Guston, or Jean-Michel Basquiat feel the same way about making art as I do is an indicator to me that I'm on the right track.

I was curious how Jimi's audience reacts to his paintings. As he pointed out to me earlier, the strong diagonal line in his work comes from his love of aviation, and I asked him if he's ever felt the need to discuss his paintings in any other representational terms.

JG: "No, but it's a valid question. It depends on what kind of mood I'm in because there's a lot I would have to reference. I try and let the person take themselves to where the work can take them, but if they need a nudge, I'd be happy to do that too."

Having to talk to the public about our work is a skill that does not always come naturally to artists. I would say Jimi is more skilled at that than I am, but I still wanted to get his take on something Gerhard Richter said in 1966. The quote goes, "To talk about painting is not only difficult but perhaps pointless, too. You can only express in words what words are capable of expressing, what language can communicate. Painting has nothing to do with that."

JG: "What a bullseye!"

To consider art making a language all its own that written and spoken language isn't capable of translating is a fascinating idea. At the same time, I've always felt the danger of relying on that idea too much. If anyone comes up to me and asks what my paintings are about, I'm not going to quote Gerhard Richter and send the person on their way. Then again, artists can't give away too much, but in Jimi's case, people aren't asking those questions anyway. As Jimi and I talked more about this, I was surprised when he told me that generally, people get stuck on the material and process and don't ask him what the work means.

JG: "Sometimes I'm itching for people to ask me what my paintings are about, and it's crazy how much I don't get asked that. Mostly people ask me about the process. You'd be surprised at how many people want to know about the process more than 'where does this work come from?' Usually, my work is not something that needs to be decoded. We're not making our paintings to be remote. We want people to engage. It's hard to get into somebody's head and wonder why they don't step up and ask more questions, but I'm ok with that."

As Gerhard Richter spoke those powerful words in the late 1960's, perhaps the art looking audience has come around to that idea. Ed Moses once posed the idea that artists are the shamans of modern society. So even though we're speaking in a language that not everyone can understand, maybe the audience of today understands better than audiences did 55 years ago. Maybe that understanding could only have been enabled with the rise of the information age that we've been living in since the turn of the century. With all the visual bombardment that advertising throws at us every day through our TVs, phones, and computers, perhaps the joy of looking and the fascination of mystery that art can offer is now, finally, enough.

After my visit with Jimi that day, I was reassured that kinships do exist between artists, and no matter which direction information is flowing, teacher to learner or leaner to teacher, that kinship will continue to be important to artists. That night, I did not come home and start writing this article. I walked right into my house and got to work in my studio. It wasn't because of the urgency that I sometimes feel. I can shake myself into a nervous wreck thinking that I don't have enough time to make work (I feel that more often than not, unfortunately). No, it was the ecstasy that I feel in those rare times when I feel that I've connected with something important and exciting. The feeling of connecting to a continuum that's bigger than you. The feeling that you're part of a sacred tradition that all of your art heroes have contributed to, and that has existed for thousands of years. That's the journey that both Jimi and I are on. Despite how hard, bumpy, and rocky the road of that journey can be, there are those moments when you know that there isn't any other road you'd rather be traveling. I definitely felt one of those moments after my visit with Jimi that day, just as he has felt many of those moments on the journey of his career. From living and working in New York, to working with mentors like Ed Moses. I know he wouldn't trade that for anything. As for me, I just hope I'm not too far behind him on the journey, and if I am, I hope there's still time to catch up.