Through The Lens spotlights emerging and established photographers from around the world. The ongoing series is dedicated to offering unique insights in varying areas of photographic expertise including portrait, landscape, fine art, fashion, documentary and more.

“When I was eight years old and my parents took me to England. We were out walking in the countryside near a manor and the guide said to me: ‘See how the land is so flat here, this used to be a jousting ground,’” said Andrew Moore.

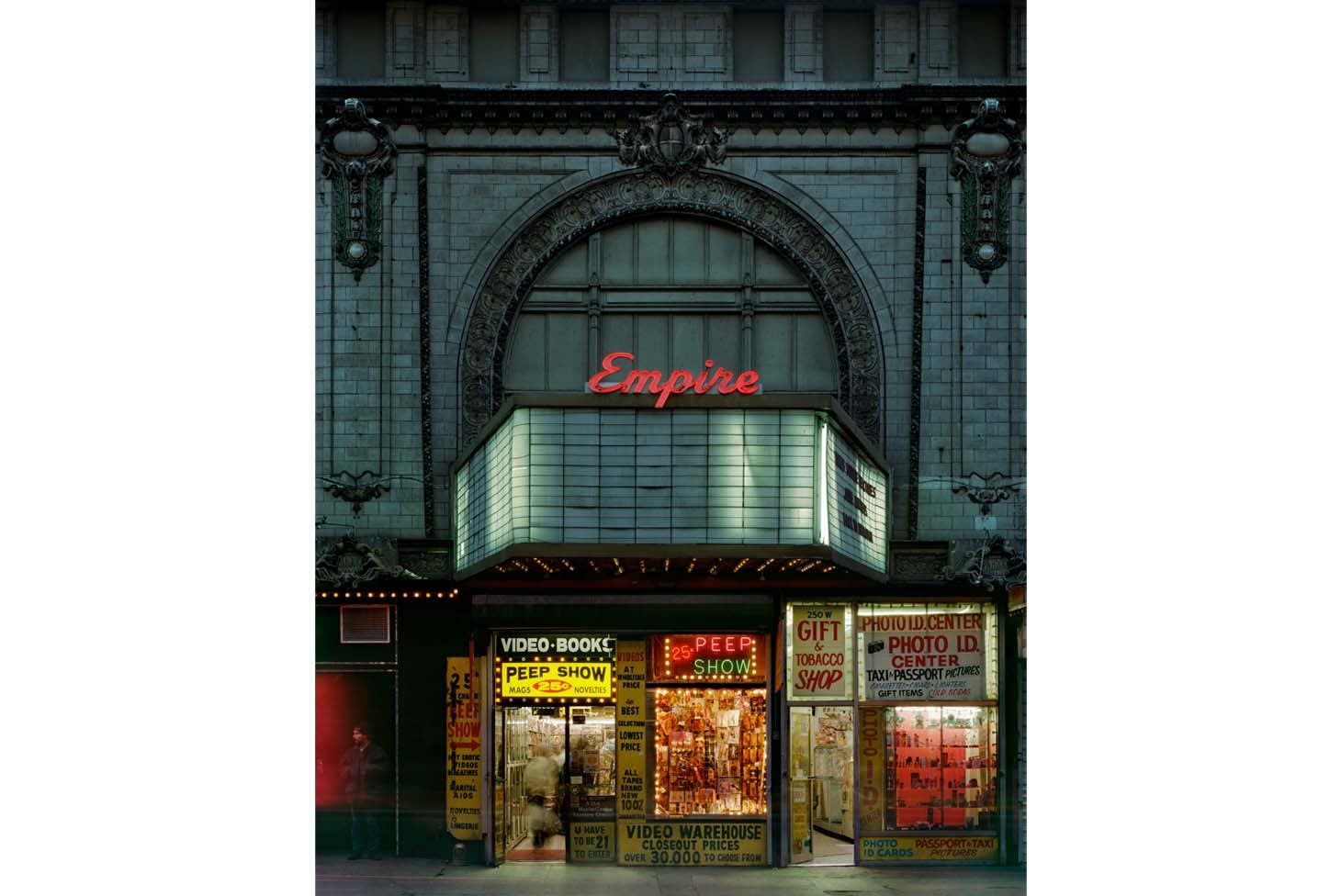

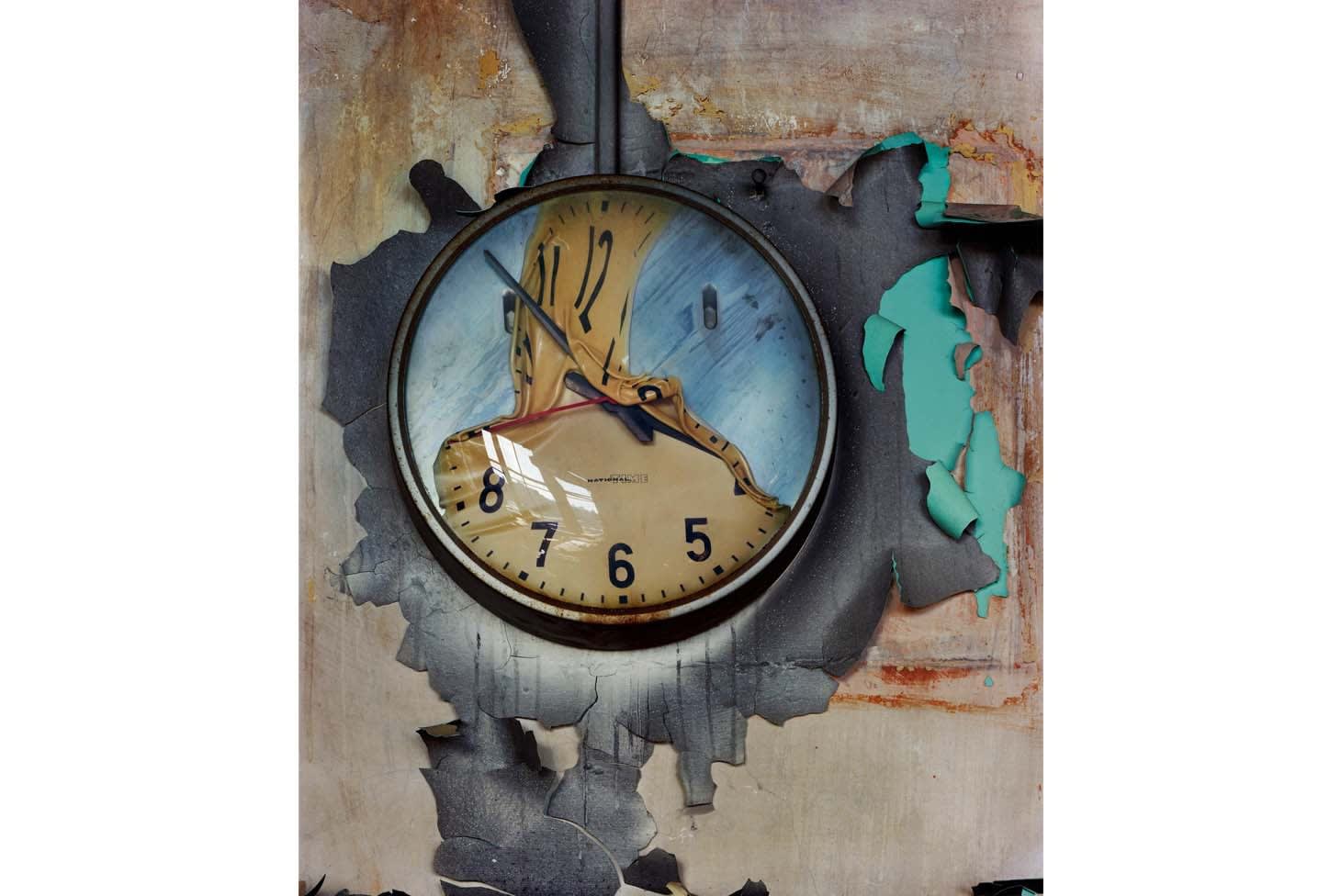

Time is a central focus for Moore, a New York-based photographer who investigates the natural and built environment. From Cuba to Detroit, Russia to Ukraine, Moore has documented the intersections of history as it unfolds and overlaps — framing the collapse of empires and the birth of new beginnings.

Moore’s photographs are held in a number of prestigious collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Yale University Art Gallery, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Library of Congress.

Amongst his many cinematic series, Moore documented both Ukraine and Russia at a time of relative peace. As Russia’s invasion of its neighbor continues, his work takes on added resonance. I caught up with the photographer to unearth his practice and reflect on our current place in history as part of the latest installment of Through the Lens.

What subjects interest you as a photographer?

I employ a wide range of subjects and places, generally of an architectural orientation, in order to create images of historical resonance. It has been said that “architecture is the incorruptible witness of history,” and in my pictures, the viewer can witness the process of conflation, the collapsing of past and present within the contemporary world, as crystallized in a single image.

Since these subjects often reflect on temporary conditions and moments of flux, or violent ruptures of time and place, one of my underlying interests is the perpetual struggle of humans to adapt and respond to historical, cultural and political shifts.

Do you have a go-to set up, in terms of camera?

I use a Phase One digital back on a Alpa 12max technical body with a variety of 4×5 view camera lenses which allow the greatest possible movement. In terms of speed, flexibility and weight it’s certainly the best set up I’ve ever worked with.

How about digital vs film?

What keeps photography alive and relevant is that it keeps evolving, so in that perspective, digital is not only another chapter in the long history of photography but also a methodology that allows us to do things differently than were done in the past.

That said, the discipline I acquired over many decades of shooting large format film has certainly benefited my recent work in high resolution digital. And in terms of color printing, which is paramount to my work, I feel especially lucky to be alive at this moment in time and enjoy the finesse and freedom possible with the digital process.

History is ever-present within your work, where the passing of time or of specific moments is captured. What first gravitated you to this form of storytelling?

When I was eight years old and my parents took me to England. We were out walking in the countryside near a manor and the guide said to me: “See how the land is so flat here, this used to be a jousting ground”. Whether or not this was true, it struck me as a kind of magic. I had something of the same feeling when my father, an architect, used to take me on visits to building sites. He would point on an empty slab and say “this will be a gymnasium one day”.

Both experiences stayed with me because they left space for my imagination, which is exactly the same kind of feeling I want to evoke in the viewers of my photographs.

You’ve traveled across the globe capturing a sense of decay from Detroit to Cuba to Russia and back. Can you describe the similarities and differences within each?

The busy intersections of history, in particular locations where multiple tangents of time overlap and tangle, have always lain at the heart of my photographic interests. In places such as Cuba and Russia, these meanderings of time created a densely layered historical narrative; in Detroit, the forward motion of time appeared to have been thrown spectacularly into reverse, especially in the late 2000’s.

Of these three projects, certainly the most significant difference was that in Detroit I felt like I was playing on the home field, and that there was more at stake for me, as an American, in getting to the heart of the matter.

Is there a particular project or series that has been most special for you thus far?

I would say that the Dirt Meridian series is especially meaningful to me. First, for the absurd challenge I took on of photographing not only the physical but also transcendent dimensions of Emptiness, second, because it took the longest of any of my projects (ten years), and lastly, because I got to spend hundreds of hours crisscrossing the High Plains in a Cessna 180.

Can you describe your experience creating the Russia/Ukraine series. What were the underlying themes explored?

I was quite familiar with both the history and culture of Russia before I arrived for the first time in 2000, but I hadn’t yet linked that knowledge to the more intimate understanding one gathers on the ground and in person.

There is an amazing story of the poet Anna Akhmatova, standing in a long line of women outside a prison during the Stalinist purges, all of them waiting in the remote hope of possibly seeing their jailed husbands. A woman that was standing behind her knew she was a famous poet, and whispered to her: “Remember this for us.”

Perhaps more than any other country, Russia is a place where history weighs mightily, and every individual’s memory is laden, if not burdened, with the past. So I would say that despite what I knew of the country’s history before I went, the most crucial and enlightening ideas were gathered from the stories people told me.

With regards to overall themes, I had two guiding principles. The first was to avoid as much as possible any well-worn stereotypes. There are very few pictures of big housing blocks in my book (and none of Red Square) because these seemed like the most ready-made and clichéd images of life in the former Soviet Union.

Instead I tried to work more around the edges of things, and in fact many of the places I photographed were actually located along the periphery of the country. I ended up shooting points east, west, north, and south but not so much in the middle of the country. This worked out rather well, as one of Russia’s great historical problems has been a lack of clear boundaries with which to define itself (as its history has shown over and over).

The second idea was the use of contrasts, by which I mean subjects that present a multilayered pattern of use and history. For example, I photographed a former synagogue that had been turned into a radio station, a monastery used as a gulag, a nobleman’s mansion transformed into a children’s theater. Russia abounds in sites that present a cross-section through time. The contradictions of these places not only address Russia’s complex past, but also, on a greater scale, the compacting and collapsing processes of contemporary history.

Considering the terrible situation now surrounding the war, how do you look back on that series?

When I was in Russia and Ukraine, back in 2000-2004, it was an in-between time: Putin had just come to power, but it was his early days, and the Russians were glad to have a ruler who wasn’t already on his death bed. In the port of Sevastopol, the Russian and Ukrainian fleets were moored side by side, the two navies were actually sharing the same base. There were disagreements between the two countries, mostly on matters of cultural identity, but not, as far as I could notice, about territorial claims. So it was a relatively peaceful time between the two countries.

As there are always proverbial good and bad people on both sides of any war, can you describe your experiences with the people of both Russia and Ukraine?

It might be strange to say, and perhaps it’s in the nature of sprawling lands, but I found the people of Russia, in person at least, very similar to Americans: big-hearted, generous and quite fun-loving. However, their public faces were quite somber and unemotional, and we used to joke that if you ever saw someone smiling in the metro, they had to be a tourist.

If, as a Czech friend recently said to me, ‘Russia is the Empire of Lies,’ then one really has to have two faces to survive in such a country. This war shows that the people of Ukraine, having lived under such an empire during Soviet times, would rather die than return to that way of living.

It’s been quite some time since you’ve commercially dabbled in filmmaking. Is this something you’re still working on today or will soon?

I’m very proud of my movie “How to Draw a Bunny”, a documentary about the artist Ray Johnson, although the experience of making the film was bruising to say the least. I continue to shoot quite a bit of video, especially with drones, and most likely will make a kind of behind-the-scenes film for my next project.

Is there a particular project, book, or exhibition we can look forward to in the near future?

I’ve been shooting a new body of work in the Hudson Valley over the past couple of years and plan to exhibit it... in Chelsea in early 2023.